The second phase of Operation Overdue - identifying the victims, liaising with families and repatriating remains - involved 10 times as many police as the ice phase and took much longer.

And while lower-profile than the recovery work, for those taking part it was undeniably confronting, emotional and difficult.

The task saw 120 police drafted in – many had undertaken DVI training and some had been on standby for the ice recovery phase.

They were assigned to teams including Body Movements, Body Reconciliation (Intel) and Inquiries. They worked with pathologists, dentists, photographers, fingerprint experts, radiographers and mortuary technicians, based at the new Auckland Medical School mortuary.

Victims’ bodies started arriving by RNZAF Hercules at Whenuapai, north of Auckland, from December 6. Initially, recognising public and media interest and family sensitivities, they were carried to the mortuary in a convoy of military ambulances and hearses. Later they came in refrigerated trucks.

The pressure was on from the moment the first arrived. As well as facing thawing and decomposing remains, police had to liaise with grieving families.

Meanwhile, the Japanese Embassy was pressing for release of the 24 Japanese visitors among the 54 overseas victims for the customary swift traditional farewell and burial.

Porirua Constable Alan Campbell was one of those drafted in. He was just 24 but had recently done DVI training. He also had a longstanding interest in aviation, had 200-plus flying hours and had read many air accident reports.

Like many others he remembers exactly where he was when he heard about the missing flight, and how he reacted that night when advised he was on standby to go down.

“I was young, part of me thought it might be a bit of an adventure. It was the chance of a lifetime to go to Antarctica.”

Instead he was told to get ready to work in the mortuary. It seemed a bit of a consolation prize, he says, noting that “at that stage I had no idea what was involved”. Nor did he, or others, know how long it would take. He told his fiancée he might not be home for Christmas.

Al was there when the first transport vehicle backed in the next day. The mortuary had been designed with disasters in mind. The ground floor housed refrigeration units for a chiller but could be extended so the entire area became a cool room.

Pathologists opened the body bags and did an initial assessment, prioritising those to be taken to the first-floor autopsy room.

“That first shift was a long one,” Al recalls. “After that they decided we would work an eight-hour day split into two shifts of four hours. That was quite a relief.”

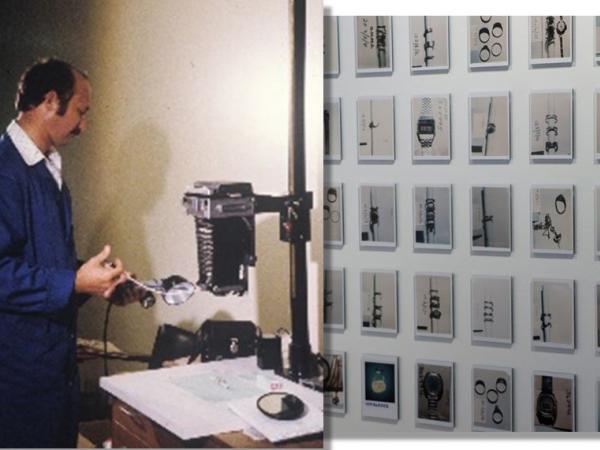

The processing room, designed for teaching, had four rows of side-by-side tables. Staffing was four pathologists and eight DVI-trained police, as well as fingerprinters, dental technicians and morticians. Photographers took 1500 pictures.

As each body arrived, Al and the others would strip it, check clothing labels for country of manufacture, remove and bag all personal items such as watches and jewellery, and record everything on the DVI form.

Pathologists would look for scars, tattoos, injuries and so on. All were ‘identified’ by grid number relating to where they had been found.

The DVI processes were new and relatively untested. “We were making up the rules as we went basically, evolving and streamlining what we had.”

It became more confronting when the pathologists started internal assessment, looking for identifying characteristics such as missing gall bladders or kidneys, and taking tissue samples which Al would send away for analysis.

Once finished, the body would be wheeled away and the next one laid out on the table. Meanwhile the pathologist would move to the next table and the process would start again. It seemed never-ending.

From 6-9 December, 114 post-mortems were performed. A further 110 - and 123 body part examinations - were performed from 12-18 December.

Al says “fascinated horror” describes what he felt. While he’d attended his share of fatals, he’d never seen an autopsy before. Bodies ranged from full to partial, slightly singed to charred.

It didn’t affect him immediately, though some didn’t get past day one. For others, the smell of aviation fuel clinging to many of the bodies could trigger memories. But Al was a flyer, and used to that.

However, the sight three years later, at Christchurch Airport, of an Air New Zealand hostess wearing the same international uniform he’d seen on a TE901 victim in the mortuary undid him. Subsequent commemorations and anniversaries have also proved confronting.

“It certainly rocked me when that happened and I’ve basically dealt with that for the rest of my life,” he says. He knows that’s true for many colleagues.

“I don’t mind talking about it because it helps.”

Alongside those assisting the pathologists were other teams responsible for fingerprinting, photography and reconciling personal effects with individuals.

Then-Constable Roly Williams, from the Inquiry Office at Avondale Station, was one of those liaising with families to aid identification.

This involved ante-mortem inquiries - asking next-of-kin about potentially identifying scars, tattoos, dental work and so on, and collecting hair samples and fingerprints from items belonging to the deceased. This would be collated with mortuary data.

The post-mortem phase saw them take photos if appropriate, items of jewellery and clothing samples to next-of-kin to see if they could identify them.

Roly makes the point that work in this phase was just as confronting as, although different from, that on the ice – with the smell of decomposition mixed with aviation fuel in confined spaces.

“At times it was overwhelming. I was 23, standing in the mortuary looking at rows and rows of bodies.

“But we had to work it out somehow. I rationalised it by thinking each one had only suffered one death. For each of them it was the same as a single fatal motor accident. It just happened to all of them at the same time.”

It was all dirty work, he says. “But it was an operation where everybody felt they were doing something useful and helping the families, though at times it was emotional and difficult.”

While other operational groups were relieved, the inquiry team worked until February. Many formed strong bonds with the families they liaised with in a task that proved fulfilling for both sides.

Leading this phase in the early days was Chief Inspector – later Assistant Commissioner - Ian Mills who, with Bob Mitchell, had helped develop the DVI capability after a study trip to America.

An assignment planning a royal tour prevented him seeing it through. Not well enough to take part in anniversary events, he recounted his thoughts to Ten One through his son Wayne, also ex-Police.

Ian always regretted that being called away denied him the chance to thank the team personally – and tell them how proud he was of them.

“He was extremely proud of their attitude and resilience,” says Wayne. “It was the single biggest job he did, not only for the circumstances but also because it had never been done on that scale before.

“He was proud of how seamlessly the various phases worked.”

The mortuary phase took nearly 15,000 hours of police time. It identified 214 of 257 victims, one of the highest identification rates for an air crash at the time. Of these, 115 were directly attributable to the dentists.

Unidentified bodies were buried in 16 caskets at Waikumete Cemetery in Auckland on 22 February 1980.

Mt Erebus remains the final resting place for some. Antarctic Special Protected Area No 156 Lewis Bay, Mt Erebus, Ross Island, is officially classified as a tomb.

In 2006 the New Zealand Government instituted the New Zealand Special Service Medal (Erebus) to recognise all involved in the recovery, victim identification and investigation phases of Operation Overdue.

A permanent exhibition honouring the victims of the Erebus tragedy and those who worked on Operation Overdue has been unveiled at the New Zealand Police Museum, Porirua.