Evidence wasn’t what they were there to look for, but Constable Stu Leighton knew he’d found something significant the moment he picked up the black folder, metres away from the shattered fuselage on the slope of Mt Erebus.

Just how significant it was wouldn’t become clear for another two years – and ironically that would be not because of what it contained, but what it didn’t. It was the Captain’s diary.

Stu had already picked up several diaries on the mountain, as the ever-present winds redeposited snow from one area to another and uncovered material in previously-searched areas.

One, he says, is still imprinted on his brain. The writer, clearly using a diary kept for travel, was following on from descriptions of earlier trips and writing as they flew. The last words were ‘Gee it’s great to be alive.’

“We were finding lots of diaries, but that was pretty poignant,” Stu says. ”It humanised everything.

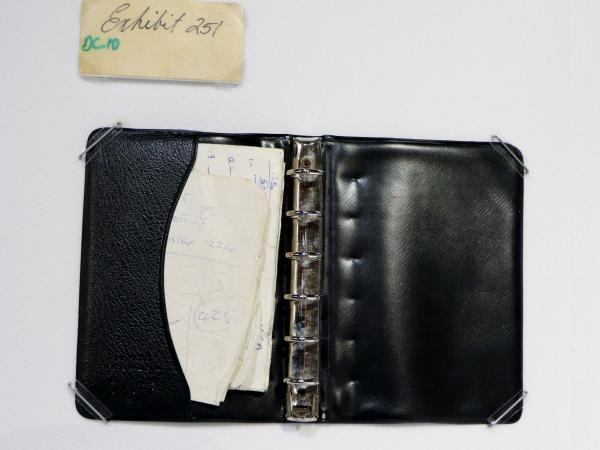

“Then I found the next one, a ringbinder with Captain Jim Collins’ name on the cover. I was instantly drawn to the fact it contained a whole lot of handwritten technical notes… which appeared to be latitude and longitude data and what seemed to be radio frequencies.”

It was just uphill from Captain Collins’s body, still in uniform and relatively unscathed, and his empty briefcase which site co-ordinator Greg Gilpin found frozen into the ice.

“I recognised it could be a very important document,” Stu says. “It contained flight data. I knew what I had.”

He took it to Greg, who recognised its importance instantly, and that they should take it to the point designated for any documents they found. Destined for the Chief Inspector Air Accidents Ron Chippindale, the diary would be helicoptered back to McMurdo.

“I didn’t really want to walk back up the mountain, but we stopped everything," says Stu. "Greg double-bagged it and then deposited it in the tent area set aside for this purpose. Then we went back to work.”

Investigating the crash was not what they were there for. Initial briefings at McMurdo had made it very clear to the DVI teams that their role was purely body recovery. “We were not treating it as a crime scene, as it probably would be today,” says Greg.

It’s clear that Greg has revisited his actions many times since, wondering whether he should have kept hold of the notebook. What became apparent some time later - that someone had removed the pages containing the flight data – haunted them for years to come.

“I had no idea that anyone would interfere with it as they clearly did at some stage after it left the mountain,” he says.

“We believed it would be in the hands of the right people at McMurdo investigating the cause of the crash. We treated it as we had been instructed to.

“There was no air crash investigator on the mountain I could have given it to. I had no other choice. We were cut off.”

History records a long and acrimonious process of apportioning responsibility for the crash. First came the Chippindale Report, and its finding of pilot error, followed by the report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry (the Mahon report) which exonerated the pilots.

Most famously, Justice Peter Mahon described some of the evidence he was hearing as an “orchestrated litany of lies”. The Mahon investigation also prompted legal process canvassing High Court and Privy Council decisions.

Neither Greg nor Stuart was interviewed by crash investigators nor called to give evidence at any point.

It wasn’t until after the Royal Commission reported in 1981 that Greg realised what had happened. The moment came when watching a television documentary about the inquiry, in which Justice Mahon was “rubbing the ringbinder on his top lip and asking an Air NZ pilot where he supposed the pages had gone”. Despite his and Stu’s adherence to instructions on how to treat such items, pages had been removed.

“If we’d had the chance to give evidence, we would have confirmed Justice Mahon’s suspicions about the ringbinder,” Greg says.

Greg tried unsuccessfully to interest others in the evident tampering, and get action. So he wrote to Justice Mahon, who then interviewed both Greg and Stu. The judge was in no doubt that the ring binder they had found was that which Captain Collins used for recording flight details.

“There is little doubt that someone from Air New Zealand got possession of this ring binder notebook, either at McMurdo or Auckland, and removed the pages. The reason for this would have been that the flight information, which you saw, represented the incorrect navigation data which Captain Collins was given at the briefing for the fatal flight,” he said in a letter to Greg.

Eventually an Air New Zealand employee acknowledged removing some pages. However it could not be conclusively established why, and whether the relevant pages were amongst them.

“But why would you remove pages from the notebook kept by the captain of an aircraft which had crashed with the loss of all lives, no matter what it contained?” Greg says.

The issue of the missing pages from Captain Collins’s ring binder notebook has never been adequately explained.